ESSAYS

ESSAYS

It is without a doubt that technology has become especially pervasive in all aspects of daily life. From a screen little wider than 6 inches, we can email, text, order, comment, ask questions, get directions, connect with others, and generally go about our day to a curated soundtrack of our lives.

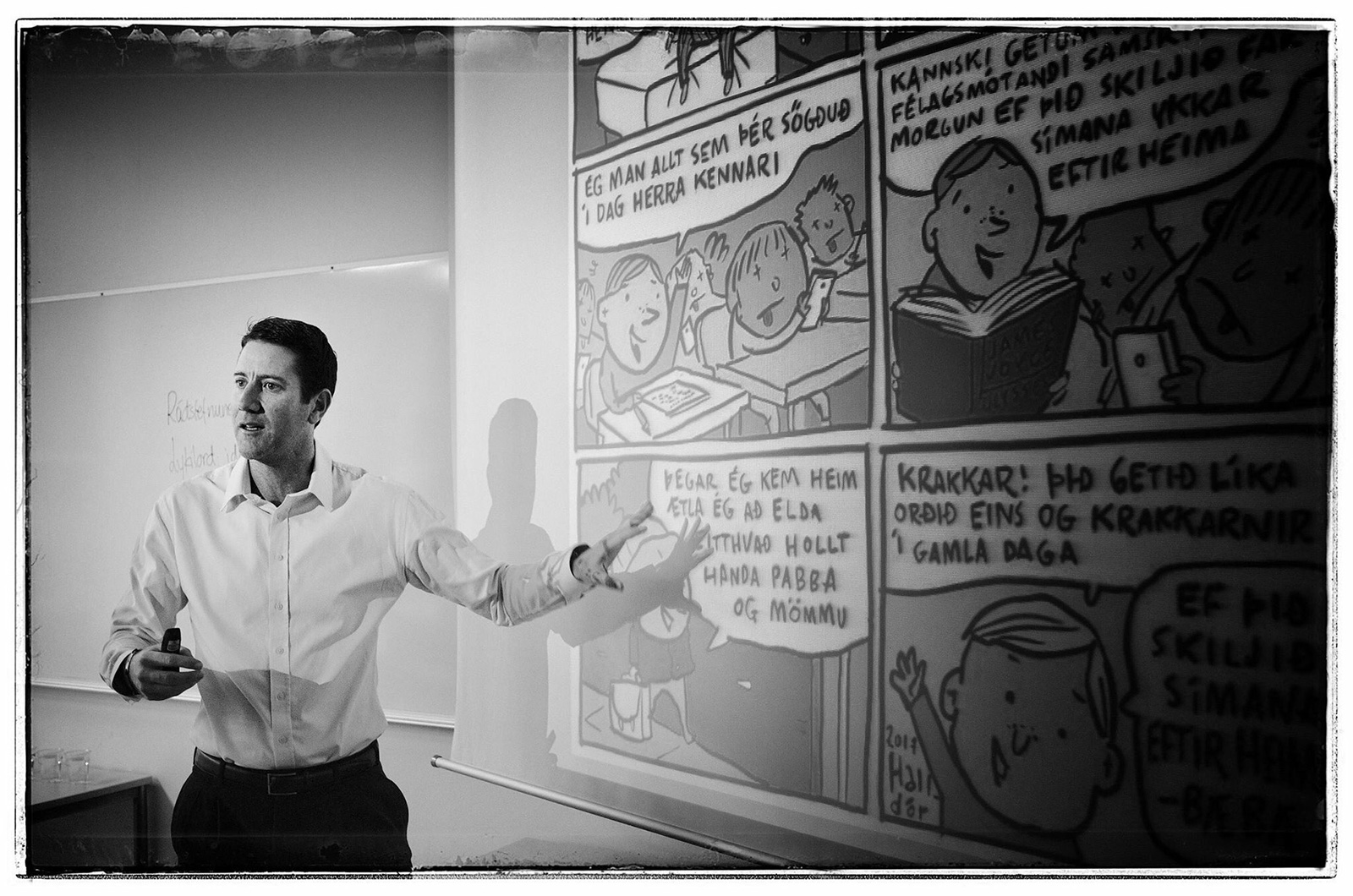

So why is it, Dr Zachary Walker wonders, that schools are the one place where we don’t allow mobile devices to be used?

“School is the one place where we should be teaching kids to use the devices appropriately, responsibly and also, for how powerful they are. We know they will use technology in every area of their lives, and often times we get upset when they don’t use it appropriately, but we do not take the time to teach them.”

As Dr Walker, an Assistant Professor in the Early Childhood & Special Needs Education Academic Group, believes, there is a need to think of a mobile device the same way we think of a pencil: a tool, but a really powerful one that we model and show how it can be used effectively.

The reality of education today is that nearly every student grows up with a mobile device, which they can bring anywhere and from which they can get any information at anytime. A big part of being an effective educator today is simply recognising this reality and figuring out how to prepare students for it. To Dr Walker, an effective educator at any point is in touch with the reality of the time.

And time, as with technology, is not known to wait. As technology progresses at an exponential rate, the education landscape in Singapore is seeing transformations of its own to keep pace. But these changes, Dr Walker observes, are still happening in pockets and are more school-specific than nation-wide. While there are teachers willing to try and do something new or different, it is important for school leaders to allow these teachers to step out of the box. In bringing technology into the classroom and letting every student have a mobile device, the educator has to be willing to give up a small degree of control, to allow students a little autonomy over their learning. This is an incredibly daunting idea for many teachers, especially knowing that their school leaders may not support them.

People in general are resistant to change. Education is highly resistant to change because we were only ever taught one way, so we naturally think that is the way teaching should be done. 20 years ago, students only had three sources of information: the teacher, the textbook, and their peers. Today, students come into the classroom with millions of sources and can find anything they want to learn online. Today, a teacher who simply gives out content has been effectively “outsourced by YouTube”, as Dr Walker succinctly puts it. Teachers have to be facilitators, to create conversation and to go deeper than the surface level of knowledge. And it is not only about facilitating knowledge and preparing students to be future-ready, technology in the classroom is also about accessibility.

“Technology, more than anything else, allows that silent kid to have a voice. It allows the kid who has dyslexia to express not only what he thinks but what he knows,” Dr Walker says. “We would never tell a child coming to class in a wheelchair to leave it outside and not use it in here. Yet we take these devices which can be incredibly helpful for our students with disabilities and say they can’t use it in here. Just because we can’t see a learning disability, doesn’t mean it isn’t there.”

Of the schools that he has observed to have embraced technology as a teaching tool, Dr Walker points out that it largely starts with leadership. Instead of focussing on worst-case scenarios and those against change, leaders at these progressive schools focus on the top percentage of teachers who are willing to go outside of the box, and provide teachers with the resources they need to succeed. When these teachers and their students advance to higher levels, the rest of the school rises up to meet it.

For teachers who are willing to go outside of the box and take the extra steps that are needed, it may not always involve technology in every instance, for every student. One school in Iceland adopts a system of skills mastery, where students have to master a list of 100 things in order to graduate. This example of differentiated instruction and individualised instruction acknowledges the reality that every student has different paces of learning and different learning needs. The teacher is there to guide the students, but how they master the 100 things and how they figure out the way to do it are up to them. And most of the time, they would turn to the internet.

Technology has given students new ways, new avenues to learn. So why not harness its power in the education system? One example Dr Walker always shares to help teachers understand the power of technology is learning about the human anatomy. What if you could put on a shirt that lets you observe how your skeletal and muscular system move in real time or watch how your digestive system works when you eat something? Now with augmented reality and mobile devices, this immersive way of learning is perfectly possible.

It isn’t about technology all the time, Dr Walker emphasises. A good teacher knows when to sit their students down and tell them a story. But, the reality is that students are going to live and learn through technology. It is a good educator’s responsibility to harness the power of technology and model its responsible use, and teach students how to use mobile devices appropriately.

Think about handwriting. How often is it used outside the classroom? It has been surmised that much of what we learn in school will be highly irrelevant in our future jobs. In the world of working adults, most of us email, text or type. Handwriting is crucial for neural development, so it will endure as an educational mainstay. But, what if handwriting is the only option for a young student struggling with dyslexia? Could we potentially be turning that student off learning for life by insisting on handwritten notes or assessments? Dr Walker believes, as a system, we have to think about other options. We have to afford more flexibility in how we allow students to express their learning, whether it is through writing, typing, or making a video. This student-produced model, in Dr Walker’s opinion, is the next big thing. We have to get students to produce information, instead of just consuming it. For teachers who are using photos and videos on mobile devices to share content with their students, the next step up is student-produced photos and videos with conversation as a back channel.

Dr Walker acknowledges there is a fear that technology will soon replace teachers. But it won’t happen because at the end of the day we are always looking for a connection, he explains. Face-to-face interaction is a more powerful experience because humans are built on connections. So there will always be a place for the teacher who can connect with students and remain in touch with reality. One question Dr Walker always asks of teachers is, ‘Would you want to learn from you?’ “If teachers keep that in mind, it helps us to reframe how we teach,” he says. If educators have this mindset of constantly learning and changing to stay relevant, the mentality of education as a whole would change significantly.

A lot of this starts at the top. School leaders have to be as willing to allow teachers some autonomy in their classroom as teachers are willing to give up some control and let students have autonomy over their learning. School leaders need to allow teachers to try, and most importantly, try again. Because innovation happens through a thousand failures. Innovation cannot be mandated; we can only create the conditions that allow it to happen. It is important for school leaders to create a culture that allows teachers to have autonomy, to try new things, to make mistakes, and to try again. If teachers fail and give up, Dr Walker says, what does that teach our students? That is what we model for our students when we act that way towards technology. And it is the same coming from a leadership level.

Culture change can also be bottom up. “Try one thing. Master that one thing and then try another thing,” Dr Walker advises. “Bottom-up change happens by this teacher trying one thing, the math teacher trying another, the science teacher trying one more, and then they share what they’ve tried. One thing at a time.”

And what about naysayers who believe giving students mobile devices in the classroom will lead to distractions and inappropriate content? Dr Walker contends that it is our job as educators to help students understand, when they come across something inappropriate, they should not be looking at it. This teaches self-discipline, as opposed to not looking at it simply because the teacher told them so. The thing about self-discipline is that it leads some students to start questioning their teachers, most of whom would find this terrifying. But, as Dr Walker sees it, “The world is changed. The reality is that they are going to have mobile devices. So we have to teach them when to use it and when it’s better to put it down and just look up at the stars. Because that’s a pretty powerful experience, too.”