What happens when three avid gamers are tasked to design a learning experience for Character and Citizenship Education (CCE)? Mr Ang De Rong, Mr Peter Bruce Gale and Mr Tee Shao Hong from the Postgraduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) (Secondary) (Class of 2020) programme tell NIEWS why they’ve eschewed traditional flipped classroom presentations in favour of creating a card game.

We all learn something from the games we play, even when there’s no intention of doing so. For example, ‘Democracy 3’ showed us the considerations behind government policies, ‘Kerbal Space Program’ had us solving equations about escape velocity and kinematics, to land a rocket on the moon while ‘Cities: Skylines’ gave us a crash course on transportation engineering and urban planning strategies. We wanted to recreate this euphoric experience of accidentally learning something in a game for our CCE class.

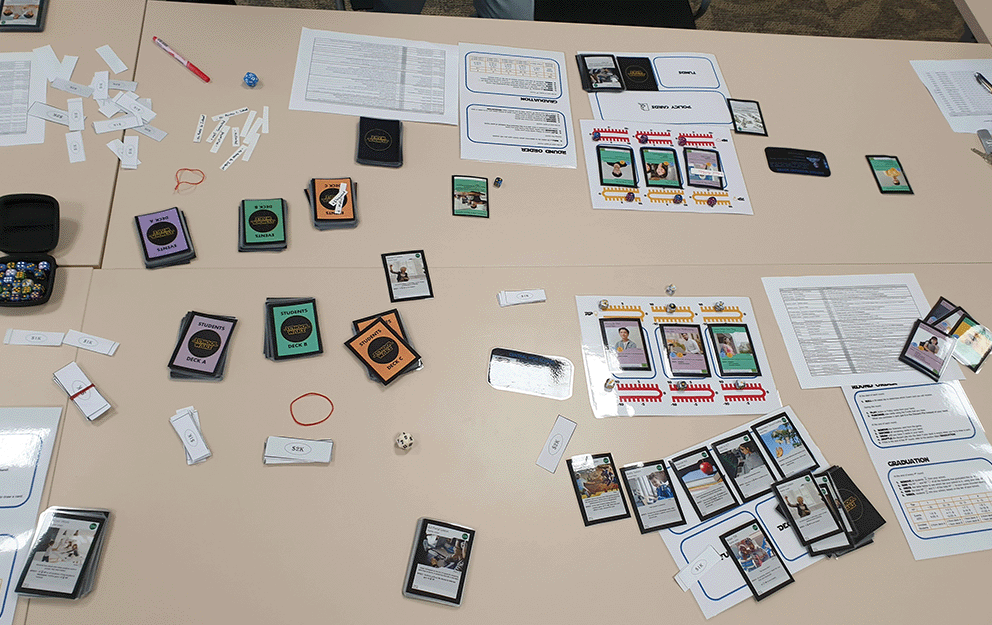

Our final product is a deck-building card game called ‘School Wars’. In the game, players role-play as the teachers and school leaders. Each school is allocated students, whose academic and non-academic developments are depicted through Academic Points (AP) and Non-Academic Points (NP) respectively. Throughout the game, using a deck of cards, players get to take actions that help or inhibit the development of their students, use funding to acquire better actions for their deck, or react to events that are happening to their students. After a set number of turns, the students will graduate, new students will come in, and players will tally up the AP and NP of their graduated cohort to add to their score. After three cycles of graduation, the player with the highest score will be declared the winner.

What the players do not know is that the odds are stacked against some of them. On the surface, everyone has the same number of cards at the start and equal access to cards that can be purchased. However, as the game is a deck-builder, we are able to manipulate the odds of having beneficial events or students with good starting AP and NP such that some players are more likely to achieve better outcomes. Players with minimal obstacles tend to acquire the good cards as they are able to focus on nurturing students and get good funding, while players with poorer odds would have to focus on solving problems at every round with little capacity to devote to student development.

We chose the deck-builder format for ‘School Wars’ as we can set players at different starting lines while maintaining an illusion of fairness within the game mechanics. As deck-builders have a significant probabilistic element, players who are disadvantaged at the start have the chance to catch up, but it is the players who have a good start who tend to end up in a better position. We wanted to show how equality does not always translate to equity, how the student’s environment often stretches beyond the school, and how we as teachers can still have an impact on students even if there are elements in a student’s environment that are out of our control.

The feedback we received after the session was astounding. Many of our colleagues enjoyed our innovative take on the subject and were highly engaged while playing the game. Some said that the gameplay caused them to realise something about inequality, and the impact that a student’s environment has on the student. We believe that ‘School Wars’ provided a simulated experience that felt genuine to our players, and this motivated their interest to learn more about CCE.

The success of ‘School Wars’ can be largely attributed to how we designed it primarily as a board game, instead of a gamified version of a presentation. Some gamification methods involve adding bells and whistles to a tried-and-tested method of evaluating learning outcomes, but they still feel like a quiz at their core. We decided to approach gamification not by building a gamified quiz, but by creating a fun game with an inherent potential for learning.

What makes ‘School Wars’ and other games with learning different is that the player does not start the game with a specific set of learning objectives in mind. The primary objective is to have fun. Players are motivated to perform better in the game simply because it is fun. This drives their desire to play and learn more about the game, resulting in the fulfilment of the learning objectives without the player even realising so! We hope that our experience will encourage more teachers to explore the use of gamification in education in their respective contexts. Afterall, a well-designed game that others genuinely want to play can be an effective learning experience.

Good luck, and have fun!